The National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) is taking multiple approaches to address clinician well-being. This article is based on a presentation by Charlee Alexander, Director of the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience, National Academy of Medicine (NAM), at the 2018 FSBPT Annual Meeting.

What is Clinician Burnout?

I have had the pleasure of directing the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience for the past year and a half. The collaborative has brought diverse stakeholders to the table with clinicians and created a new mechanism for organizations to share information, learn from each other, pool resources, and make a collective impact.

Burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, de-personalization, or feeling calloused or detached towards patients and colleagues, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. It leads to decreased effectiveness at work and is driven by work-related stressors.

In 2014, Liselotte Dyrbye and her colleagues at the Mayo Clinic, in coordination with the American Medical Association, conducted a survey of more than 6,000 US physicians across all specialties and practice types. They found that 54 percent of physicians have substantial symptoms of burnout, and this was up 9 percent from a study of 7,000 physicians in 2011. (Since this October 2018 presentation, a new study shows burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration among US physicians improved between 2014 and 2017, with burnout currently near 2011 levels.)

The prevalence of burnout among other US workers is substantially lower and hasn’t changed much from 2011 to 2014. Burnout is nearly twice as prevalent among physicians as US workers in other fields. Even adjusting for factors such as work hours, just being a physician is an independent predictor of burnout.

Large national studies have found a high prevalence of burnout and depression among medical students and residents, with rates higher than those of similarly aged individuals pursuing other careers. There’s also substantial evidence to support that nurses experience high degrees of emotional exhaustion, which is one component of burnout. Less is known about advanced practice providers, pharmacists, physical therapists, and other members of the health care team—additional research is needed in these areas.

Several national studies of physicians have found independent relationships between burnout and working longer hours, age, gender, and specialty. For example, for those under age 55, there is a 200 percent increased risk of burnout compared with those older than 55. Emergency medicine, family medicine, general internal medicine, and neurology have higher rates of burnout compared to other specialties. In addition, physicians with children whose spouse also works are at greater risk for burnout.

Burnouts Effects

In a survey at the New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst Council, members cited decreased quality of care as the leading reason to address physician burnout.

The literature suggests a significant effect on quality and risk of medical malpractice suits and shows a relationship between burnout and medical error. In physicians, burnout and depression are independent predictors of physicians perceiving that they have committed a major medical error, and there is likely a bidirectional relationship between burnout leading to medical errors.

In cross-sectional studies of more than 7,000 US surgeons, burnout was an independent predictor of reporting a recent major medical error and being involved in a medical malpractice lawsuit. Research shows that mean burnout levels among hospital nurses are an independent predictor of health care associated infections. Burnout scores among physicians and ICU nurses relate to patient mortality and decreased teamwork score. Additionally, in physicians and nurses, there is an association between job satisfaction and patient satisfaction, and between depersonalization and patient satisfaction.

There is also a strong associations between burnout and intent to leave practice. In large national studies, burnout is an independent predictor of physicians leaving practice for reasons other than retirement. Burnout and job satisfaction are also associated with nurse turnover. It’s estimated that the cost to replace a nurse is around $88,000, although this data is from 2007, and the cost to replace a physician can be up to $1 million. Burnout is also associated with absenteeism, reduced job productivity, increased referrals, and suboptimal ordering patterns. Additionally, as you can imagine, high rates of turnover impact access to care.

What Drives Burnout

There are many factors affecting clinician well-being and resilience. They relate to rules and regulations, the digital health environment, workload and productivity demands, loss of meaning, autonomy and control, and stigma and fear of sharing vulnerabilities. Often, the drivers highlight a lack of alignment between organizational values and personal values, and a lack of social support at work. In trainees, the learning environment and educational debt are major contributors.

Often, folks don’t feel comfortable talking about mental health. Therefore, if the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) can provide a venue for compassionate dialogue, we are willing and able to do so. We currently do this through our stakeholder meetings and art show, , Expressions of Clinician Well-Being, that calls on artists of all skills and abilities to express what clinician well-being looks, sounds, and feels like to them.

Additionally, in 2016, Darrell Kirch of the Association of American Medical Colleges, and Thomas Nasca from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, approached NAM president, Victor Dzau, to see if there was a role for the NAM to convene the many organizations working on this issue separately, to move towards targeted investment and collective action. They drafted a commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine, “To Care is Human: Collectively Confronting the Clinician Burnout Crisis.” They said, “Through collective action and targeted investment, we can not only reduce burnout and promote well-being, but also help clinicians carry out the sacred mission that drew them to the healing professions—providing the very best care to patients.”

The Action Collaborative Working Groups

The Action Collaborative launched in January 2017, with three key goals:

- Raise visibility of clinician burnout, depression, stress, and suicide.

- Improve baseline understanding of challenges to clinician well-being.

- Advance evidence-based, multidisciplinary solutions that will improve patient care by caring for the caregiver.

The NAM feels very strongly that it is not the individual who is at fault for being burned out, but the system in which they operate. And so the collaborative is looking beyond individual resilience and focusing primarily on organizational systems and culture change. This is not to say that individual solutions are not needed, they are, but the NAM is able to convene major players at the systems level, so that is where we focus our efforts.

We’ve assembled a diverse group of thirty-nine committed sponsoring organizations. To achieve our goals, we’ve organized ourselves into four working groups.

- Research, Data, and Metrics

- Conceptual Model

- External Factors and Work Flow

- Messaging and Communications

The working groups are comprised of approximately sixty-five participants across medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and dentistry, representing professional societies and membership organizations, government agencies, health IT vendors, large health care centers, payers, researchers, trainees, early career professionals, and, very importantly, patient and consumer perspectives.

As noted earlier, a clinician burnout affects the entire health care team. Therefore, we need a robust number of stakeholders for this effort, so that everyone is at the table as we develop solutions.

Research Working Group

In 2017, Dyrbye and colleagues released a discussion paper, “Burnout Among Health Care Professionals: A Call to Explore and Address this Underrecognized Threat to Safe, High-Quality Care.” In addition to a review of the literature, the authors provided three major areas for future research:

- Research to identify organizational and health care system factors that increase risk of distress for health care professionals,

- Research to gain further understanding of the implications of health care professional distress and well-being for health care outcomes, and

- Intervention research to improve the work lives and well-being of health care professionals.

The research working group also profiled several validated instruments that assess work-related dimensions of well-being, including burnout, composite well-being, and depression and suicide risk. While several instruments measuring clinician well-being have well-established reliability and validity data, they are not all equally pragmatic for use by an organization. So Dyrbye et al. published a discussion paper with a list of considerations for individuals charged with measuring health care professional well-being at their institutions to guide them in selecting the most appropriate measurement instrument.

Conceptual Model Working Group

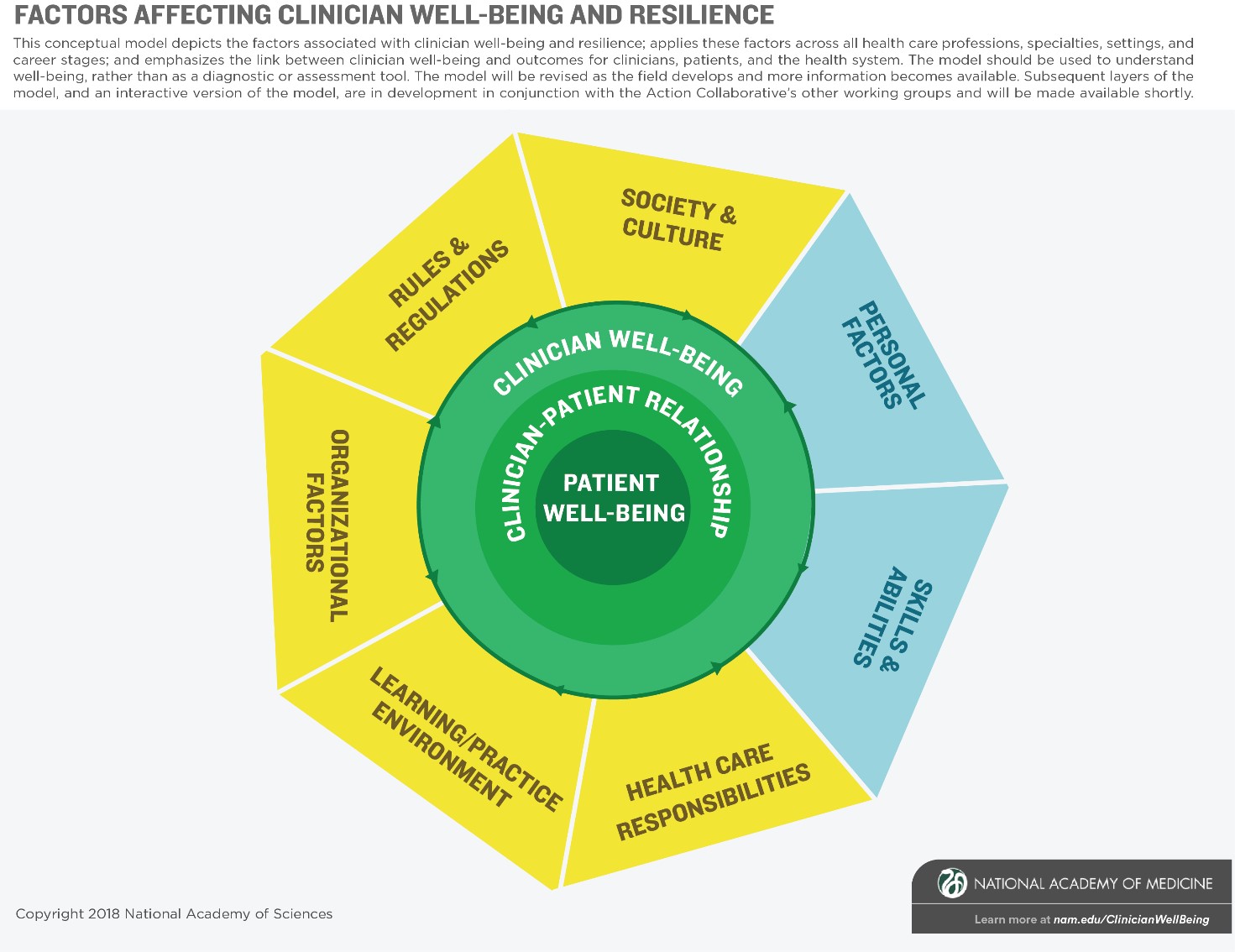

Despite the utility and applicability of existing models of well-being and burnout, the Conceptual Model Working Group did not find a model that depicts the factors associated with burnout and well-being, applies them across all health care professions and career stages, and clearly identifies the link between clinician well-being and outcomes for clinicians, patients, and the health system. For this reason, the working group developed a new model, which is not a diagnostic or an assessment tool and should only be used to understand well-being.

Starting with the outermost ring of the nucleus and moving inwards, we have clinician well-being, the clinician-patient relationship, and patient well-being. On the left-hand side in yellow are the external factors: society and culture; rules and regulations; organizational factors; the learning and practice environment; and health care responsibilities. On the right-hand side in blue are individual factors: personal factors, and skills and abilities. The more numerous external factors illustrate that external factors in systems and culture often have a larger effect on clinician well-being than individual factors.

A number of sub-factors accompany the major domains. In recognition of the complexity of clinician well-being, these elements are listed in alphabetical order. The intent was not to prescribe a hierarchy; instead, users will determine the salience of the elements on a situation-by-situation basis. We hope that the model is broad enough to define the issues across all health care professions, and that it successfully encompasses multiple environments and multiple stages of development.

External Factors and Work Flow Working Group

A recent Stanford Medicine Harris Poll asked 521 primary care physicians about the effects of electronic heath records (EHRs) on burnout. Seventy-one percent of doctors agreed that EHRs greatly contribute to burnout, 69 percent agreed that the EHR takes valuable time away from interacting with patients, and 59 percent thought EHRs need a complete overhaul. Pretty strikingly, only about 8 percent said that the primary value of EHRs is clinical.

Additionally, physicians described the amount of time they spend in the EHR versus interacting with patients. Those polled said that of the thirty-one minutes they traditionally spend on behalf of patients, nineteen were spent in the EHR either during the patient encounter or afterwards—so either later that day or when they’re at home with their families—and only twelve minutes were spent interacting with the patient.

Therefore, the first resource out of the external factors working group was a paper, “Care-Centered Clinical Documentation in the Digital Environment: Solutions to Alleviate Burnout.” The authors examine how administrative requirements and clinical documentation contribute to burnout and offer solutions to improve well-being. The paper highlights challenges and opportunities in the digital health environment and makes recommendations about how health information technology (IT) can be reimagined to support clinicians, patients, and patient-centered care.

On October 1, 2018, the group released a companion piece, “A Vision for a Person-Centered Health Information System.” The authors describe a vision for a person-centered health information (PCHIS) system through a series of vignettes; discuss components of the system such as automation and integration, the patient view, and system organization; and discuss how to optimally engage health IT for the patient and care team. The authors highlighted several barriers to achieving the vision, but recommended specific actions.

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC), vendors and software developers, hospitals and healthsystems, and clinicians should collaborate to set and implement interoperability standards including comprehensive and detailed clinical models for prioritized use cases, and vendor support for extracting and inputting data for the adopted standards.

- Vendors and software developers, hospitals and health systems, and clinicians should enhance the use of interfaced applications and services (e.g., SMART on FHIR, CDS Hooks, and knowledge representations standards such as Clinical Quality Language).

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, in collaboration with clinicians, and vendors and software developers, should refine evaluation and management documentation guidelines to reduce excessive documentation and promote the use of new information systems to their fullest potential.

- Hospitals and health systems should accelerate plans to replace legacy systems with new systems and fund their updates and the implementation of new capabilities. These new systems or updates will also require resources and time for implementation and training.

- Vendors and software developers should further develop technologies such as artificial intelligence and natural language processing, and provider organizations should test them in the clinical environment.

- To ensure the PCHIS system works for patients and clinicians, these stakeholder groups should be included in the design and rollout of these new systems.

In the paper, “Implementing Optimal Team-Based Care to Reduce Clinician Burnout,” (Smith et al., 2018) the authors outlined key features of high-performing teams, which include mutual trust, psychological safety, effective communication, clear roles, and shared measurable goals. The paper also cites research linking teamwork and patient outcomes, but notes that more evidence is needed connecting high-performing teams and clinician well-being. The authors also discussed regulatory barriers to implementing team-based care. To move forward, they suggested better aligning licensing and regulation, prioritizing training and assessment, modernizing documentation guidelines, and, as discussed above, reimagining EHR interoperability and workflows.

Messaging and Communications Working Group: The Knowledge Hub

The Clinician Well-Being Knowledge Hub is a comprehensive resource repository about clinician burnout and well-being that compiles research and resources into one location.

The hub encompasses clinicians of all professions, specialties, and career stages. The hub is an attempt to build our collective knowledge so that people can go to this resource repository to learn more and to take action.

The Knowledge Hub is organized around three main topics:

- Causes: Organizational factors, learning environment, practice environment, society and culture, personal factors, rules and regulations

- Effects: Safety and patient outcomes, clinician well-being, turnover and reduction of work effort, health care costs

- Solutions: Organizational strategies, measuring burnout, individual strategies

We have more than 900 resources in the resource center so far, and we continually update them. Resources can be searched by keyword or filtered by topic area and type of resource.

Now that they’ve completed the Knowledge Hub, the Messaging and Communications Working Group is focused on our case study series, which will highlight programs and initiatives that are engaging in promising practices to promote clinician well-being and provide actionable guidance for organizations that want to implement something similar.

We’re excited about this feature because we also plan to build a community of shared learning. We want feedback from institutions that have used the case studies to generate feedback so that we can learn what was successful and if there were tenets of the program that were unique to the original institution. We can also connect groups for a community of support.

NAM Consensus Report

The National Academies are well known for our consensus reports. The process involves committee members who come together to review the literature on a certain topic (e.g., clinician well-being) and then they deliberate for about nine to twelve months. They generate findings based on a review of the literature, make conclusions based on those findings, and make recommendations based on those conclusions. Through that drafting process, they have a number of public information gathering sessions. Once they have a final report, it is extensively peer-reviewed by experts in the field.

The committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being will examine the scientific evidence regarding the causes of clinician burnout as well as the consequences for both clinicians and patients as well as interventions to support clinician well-being and resilience. In developing the report, the committee will consider key components of the health care system, including:

- factors that influence clinical workflow, workload, and human-systems interactions;

- the training, composition, and function of interdisciplinary care teams;

- the ongoing movement toward outcomes-based payment and quality improvement programs;

- current and potential use and impact of technologies and tools such as electronic health records (EHRs) and other

- informatics applications; and

- regulations, guidance, policies, and accreditation standards that define clinical documentation and coding requirements, as well as institutional expectations and interpretations of those requirements.

In November of 2019, the committee will issue a report with recommendations for system changes to streamline processes and manage complexity, minimize the burden of documentation requirements, and enhance workflow and teamwork to support the well-being of all clinicians and trainees on the care team, prevent clinician burnout, and facilitate high-quality patient care. We hope that the report will have the same effect on clinician well-being that, To Err Is Human and Crossing the Quality Chasm had for patient safety.

We envision a campaign of systems change, of evidence-based solutions, of leveraging networks of organizations committed to improving and implementing clinician well-being, to growing a network to create a larger community of empowerment, and creating healthy clinicians for healthy populations.

The NAM’s commitment to clinician well-being is evidenced by our planned activities, which will extend through December 2020. While clinician burnout is a complex, multifaceted challenge, we are optimistic that this collective action and targeted impact will lead to improvements in the well-being of health care professionals.

|

|

Charlee Alexander

Program Officer, National Academy of Medicine (NAM)

As a program officer at the NAM, Charlee Alexander has directed the Action Collaborative on Clinical Well-being and Resilience for over 1.5 years. Charlee also co-directs the NAM Culture of Health Program, a multi-year collaborative effort funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to identify strategies to create and sustain conditions that support equitable good health for everyone living in America.

|

Read previous issues of the FSBPT Forum.